"Pioneering diabetes treatment brought my boy back from the brink"

25 January 2021

4 mins to read

Hearing your child utter their first words is an emotional time for any mother, but for nurse Emma Matthews it was a heart-melting moment she thought would never come. As her son Jack Neighbour, then five, mustered up his little voice to say “Hello, Mummy” for the first time, she listened with joy and disbelief.

Jack, who has special needs, was diagnosed with neonatal diabetes shortly after birth and had never spoken a word, communicating only through picture cards.

Now, thanks to a “miracle” treatment, Emma was listening to the sound she’d always longed to hear: her son speak for the first time.

Before that tender exchange, Jack – unable to produce his own insulin – inhabited a silent world blighted by violent convulsions, insulin injections and up to 15 finger prick blood tests, day and night.

Managing his condition had become a “living nightmare” for mum Emma and she feared he wouldn’t live to see his sixth birthday. As his blood sugar fluctuated, his tiny body was pummelled by frantic highs and dangerous lows, and Emma was clutched by the terror that the next seizure could kill him.

“We’d wake up in the night with Jack completely manic because his blood sugar level was so high, or in convulsions on the floor because it was so low,” recalls Emma. “His blood sugar levels were all over the place, and I didn’t think he was going to be alive when I went into his bedroom in the morning.”

A life-changing genetic breakthrough

Everything changed for Jack and his family, when a blood test carried out by the genetic diabetes research team at the University of Exeter Medical School identified the precise cause of Jack’s lack of insulin: a genetic mutation in a potassium channel in his pancreas.

Thanks to Exeter-based scientists, Jack stopped insulin injections and began a simpler medication of taking sulphonylurea tablets to correct the abnormal channel. The pioneering treatment triggered Jack’s pancreatic cells to release their own insulin.

The results were astounding. Within weeks, Jack’s blood sugar levels had stabilised and he had stopped collapsing. No longer held to ransom by his diabetes, Jack transformed overnight into a smiling, laughing boy. For Emma, panic-struck, sleepless nights gave way to tranquil days spent doing the everyday family stuff they’d once been precluded from.

Then, six weeks into the treatment, Jack beamed as he said his first words.

“Jack turned into a really happy little chap,” says Emma. “Before, we couldn’t take part in normal activities because we had to take so much medication and bags of sugar, to account for any eventuality. It's like we've gone from living in a horror film to living in a rom com. He will always have severe special needs, but now his diabetes just isn’t an issue. For us, it really was a miracle.”

"Before, we couldn’t take part in normal activities because we had to take so much medication and bags of sugar, to account for any eventuality. It’s like we’ve gone from living in a horror film to living in a rom com. He will always have severe special needs, but now his diabetes just isn’t an issue. For us, it really was a miracle."

Emma Matthews

Jack’s mum

A global revolution in diabetes care

Jack is not alone. Thousands of people have since successfully made the switch from insulin to sulphonylureas tablets across the world. The research led by the University of Exeter has changed international guidelines to advise that all children with neonatal diabetes should now have the same genetic test as Jack had, to see if they too can switch to tablets.

Professors Andrew Hattersley CBE, Professor of Molecular Medicine at the University of Exeter said: “Switching from regular insulin injections was life-changing for these people who had been on insulin all their life; many described it as ‘a miracle treatment’. Not only does this eradicate the need to inject with insulin several times a day, it also means much better blood sugar control.”

A decade-long analysis of the treatment, led by the Exeter team and published in The Lancet Diabetes and Endocrinology, reveals that sulphonylurea tablets are just as successful over the long-term, with excellent blood sugar control after 10 years.

Professor Hattersley said: “This is the first study to establish that this treatment is safe and works excellently for at least 10 years and all indications are that it will continue to work for decades more. This is great news for the thousands of patients who have made the switch from insulin.”

Now a young adult, Jack has since celebrated many milestones that once seemed unimaginable when Emma was fearing for her toddler’s life. “We’re so proud of our charming young man,” she says. “He makes friends wherever he goes. Dealing with Jack’s diabetes was particularly hard because of his severe learning difficulties. I honestly don’t think he’d still be with us if it wasn’t for the research at Exeter.”

"This is the first study to establish that this treatment is safe and works excellently for at least 10 years and all indications are that it will continue to work for decades more. This is great news for the thousands of patients who have made the switch from insulin."

Professor Andrew Hattersley FRS

Professor of Molecular Medicine,

Consultant Physician

Explore more research

Precision diabetes: The right treatment for each patient

The University of Exeter has led the way in making discoveries that are swiftly translated into healthcare, to improve lives worldwide.

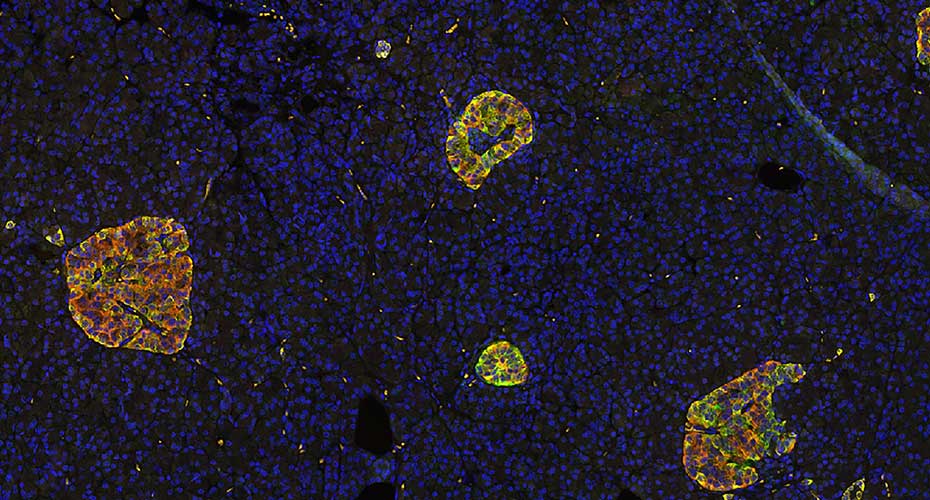

Unravelling the mysteries of the pancreas to improve type 1 diabetes diagnosis

Exeter have busted diagnosis myths and created new, simple and inexpensive diagnostic tests that are being used around the world.

Understanding type 2 diabetes, to treat all its forms

By far the most common form of diabetes, type 2 diabetes is nevertheless misunderstood. While classified as one condition, the complex disease actually comes in all shapes and sizes.