Digital Humanities gallery

The Deir Mar Musa censer

This censer is a copy made by a Syrian coppersmith of a censer held in the British Museum. The original comes from the monastery of Deir Mar Musa al-Habashi in Syria, and dates from the sixth to ninth centuries.

The censer was 3D scanned as part of the Architecture and Asceticism project, making it available widely to view and study and allowing further analysis to be carried out. Remarkably few liturgical objects have survived from the time, and its age means it can tell us much about the artistic and liturgical traditions of the Syrian Church.

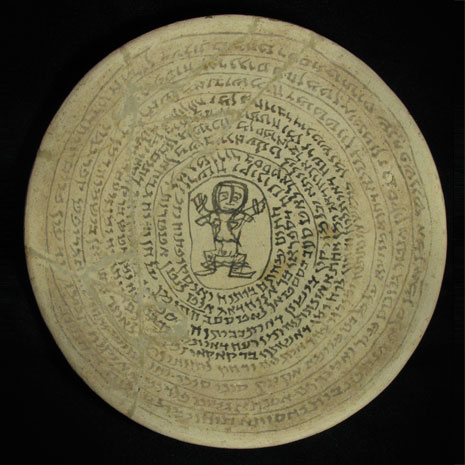

Aramaic magic bowls

Aramaic magic bowls originate from Mesopotamia or south west Iran in Late Antiquity (circa fifth to sixth centuries CE). An anxious or suffering person would visit a scribe, who wrote a personalised text on the bowl that sought protection and healing for the client.

These personalised texts give us a glimpse of everyday lives and reveal new social connections between different religious communities. The bowls are kept in collections across the world, many of them privately. Creating a digitised collection of high-quality images allows researchers instant access to a large corpus of bowls and their texts.

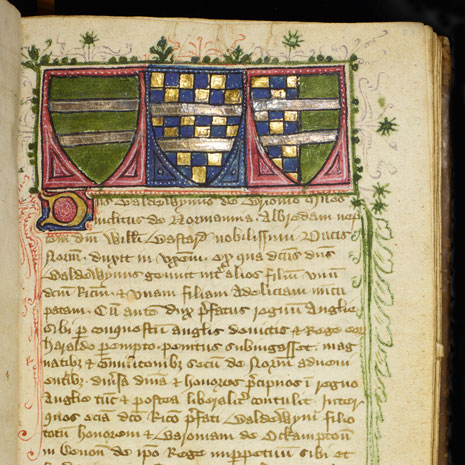

Powderham Castle manuscript

Powderham Castle is the ancient seat of the Courtenay family, Earls of Devon. This medieval cartulary contains the family tree and life stories of some of the Courtenays’ most remarkable ancestors.

The book is richly decorated, with branches of the family tree running across each page, and the coats of arms of each generation picked out in gold leaf. Digitising this manuscript will enable the original medieval “tree” to be put together for the first time, and bring to life the story of the Courtenays and their connections to key events in Devon’s history.

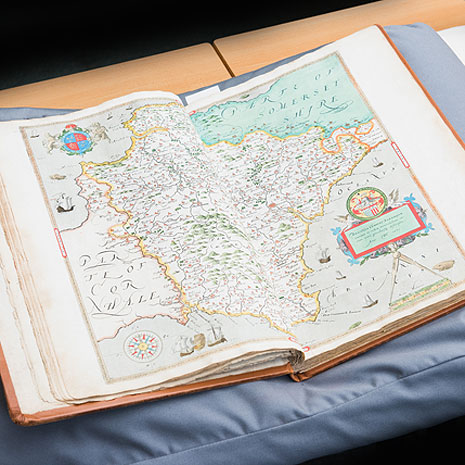

Christopher Saxton atlas

This landmark volume was the first national atlas of England and Wales. It provided a new standard in cartography when it was published in 1579, continuing to be used and adapted for the next two hundred years. It consists of 35 illustrated colour maps of English and Welsh counties.

The atlas was made possible by advances in draughtsmanship and surveying techniques, due to the needs of military engineers and the demand for surveys of landowners’ estates. Each map is printed from a copper plate that was engraved by hand. This copy is kept in Heritage Collections at the University of Exeter.

Skulls excavated at Ipplepen

These skulls were excavated at the Roman settlement of Ipplepen, in Devon. The bone preservation was extremely poor and the skulls are very fragile. To preserve them for the future, we 3D-scanned them and created a digital model of each skull.

3D scanning the skulls enables us to preserve an accurate record of the size and shape of the skull, especially key morphological features that determine sex and age. It will also enable future researchers to examine and re-evaluate the skulls. From this 3D scan, we can create a 3D replica that can be handled without the original being damaged.

Arnold Mitchell’s football boots

These football boots (left and right) were used by Exeter City footballer Arnold Mitchell from the late 1950s until 1966. They still have mud from the pitch of the final game that Mitchell played in Exeter before he retired.

The Grecian Archives project, which aims to facilitate the exploration of the history and heritage of Exeter City FC, is creating an online archive using collection management software. The project is working with the Football Club and the Supporters Trust to collect memories of the Club from local people, to preserve this important aspect of local and regional heritage, and make it available to all.

Pym football

This football was presented to Exeter City Football Club on their tour of South America in 1914. On this tour, Exeter made history when they became the first opponents of the Brasilieros XI – the Brazilian national team.

This 3D scan of the football, created using photogrammetry which reconstructs objects from multiple photographs, forms part of the Grecian Archives. Emerging research is beginning to explore whether 3D objects could be used to stimulate discussion in heritage preservation and perhaps even trigger recollections for veteran supporters with memory difficulties.

Chromatrope

The Chromatrope is a type of magic lantern slide that can produce a constantly changing pattern. The lanternist would move the handle which would rotate the coloured pieces of glass in the slide. When projected this creates a beautiful and immersive moving image. Based on Brewster’s kaleidoscope (1817), a scientific instrument that quickly became a popular children’s toy, this example from the 1840s is one of many types of slide to be found in the Bill Douglas Museum collection.

By capturing and animating at high resolution, the digital object can recreate the effect experienced by Victorian audiences.

Charlie Chaplin mask

This mask of Charlie Chaplin in his iconic guise as ‘the little tramp’ is an official piece of merchandise made in the 1970s in France. Chaplin has always been immensely popular in France where he is known as ‘Charlot’. Chaplin’s fame spread around the world from the 1910s and the popularity of his comic films, which he wrote, produced and directed, helped to establish film as the dominant medium of the 20th century.

3D scans of this mask from the Bill Douglas Museum collection can show this fragile object from all angles, and reveal details of its construction and materials.

Astronomical magic lantern slide

This magic lantern slide, probably dating from the 1830s, depicts Saturn and Uranus (then known as Georgium Sidus or the ‘Georgian Star’). It is one of a set of 23 slides showing astronomical subjects made by W and S Jones of London. Magic lanterns were often used as an instructional tool but popular shows were also keen to draw on subjects that would bring the world to the audience as well as creating a sense of wonder.

Capturing these slides in all their fine detail can preserve and protect them, allowing access without the need to handle the fragile originals, which are held by the Bill Douglas Museum.

Building collaborative communities

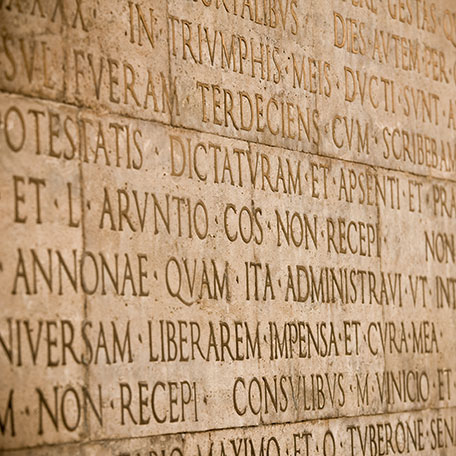

International communities are at the heart of Digital Humanities research. DH projects tend by their very nature to be collaborative, as they need people working in several different highly skilled areas in order to achieve their research aims. These collaborations are frequently international, bringing together expertise from institutions across the world. One example is the EpiDoc project, a collaborative community that provides guidelines and tools for encoding scholarly and educational editions of ancient documents. We also work with libraries, archives, museums, private collections, companies, schools, community groups and many other types of organisations to further humanities research.

Linked Open Data

Linked Data uses unique resource identifiers (URIs) to provide machine-readable canonical references for the entities that appear in our source materials. Linked Open Data is Linked Data published on the public web under an open licence. The relationships between entities are described in highly structured ways, allowing other projects to link their data to ours (and vice versa) in a way that can be interpreted by computers. The Semantic Web, made up of these descriptive connections, not only enables humans to follow links manually but also enables computers to extract meaning from our documents, enriching our network of knowledge and making our digital publications more easily discoverable.