Maru leads an interdisciplinary workshop.

Interview with a Soapbox Scientist: Dr Maria (Maru) Eugenia Correa Cano

If we lined up all the water bottles that are bought in the UK in a single year, they could go from London to Manchester and back again ten times over. And those water bottles – all ten billion of them – would not break down for 450 years, long outliving the people who bought them.

While this is clearly a problem in terms of waste, Dr Maria Eugenia Correa Cano, known as Maru, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Exeter, explains that it isn’t only waste we should be concerned about. We should think about each product we buy in terms of the impact of its whole life cycle on our planet.

In the case of the water bottle, its lifecycle starts with the extraction of crude oil (used to make plastic) and very often ends with a landfill in a few centuries’ time. In between, we have to consider the energy involved in creating the bottle from raw materials, transporting the bottle to the shop, selling the bottle, and transporting the bottle to a rubbish tip.

As part of a large project call RENEW, Maru is currently developing a tool that helps businesses and organisations understand the life cycles of their products and operations, and the environmental impact that each stage of the life cycle has. Specifically, she focuses on the impact each stage of a product’s lifecycle has on biodiversity. To stay with the example of the water bottle, Maru’s tool would break down how each stage of the bottle’s lifecycle might impact biodiversity.

“In many of the processes we use to create the water bottle, for example, we need land. This means we are removing habitat for plants and animals and decreasing biodiversity.” She explains this is bad not only for the plants and animals we share the planet with, but also for ourselves. “We rely on the biodiversity of the planet’s ecosystems to provide oxygen, pollination, protection against flooding, as a source of energy… really for everything in our lives.”

By helping organisations understand the impact they are having on biodiversity, Maru’s tool opens the way for them to decrease their footprint on nature. “Businesses and financial institutions are interested in understanding and reducing their impacts more and more,” Maru tells me. “It’s slow, but change is happening.”

Maru is optimistic that we can make big changes through small adjustments in our habits, both at an organisational and at a personal level. “It doesn’t take a huge change to make a difference, and I think it is super important people know this. Buying one less water bottle per month would make a huge difference to the number of water bottles we use in the UK in a year, and this would make a big impact on our environmental footprint. Every single person can make a difference, they just need to know that they can.”

Maru currently works in the Engineering Department of the University of Exeter. Trained in biology and ecology, as well as in community engagement, she is now combining engineering methods from a “Systems Thinking” perspective with her previous background. In this project, all of her passions come together: understanding ecosystems, our relationships with nature, how to use resources sustainably, and finding solutions to decrease our overall impacts.

It hasn’t always been the easiest of journeys though, and Maru says that for a long time she struggled with imposter syndrome, especially around her ability in maths. “I was good at maths, but I didn’t think I was. In school, I was the only girl with good marks in maths, but I was judged very harshly by classmates, so I didn’t necessarily get the encouragement I needed. I just didn’t think I was very good.”

As Maru moved further into her education and career, new challenges cropped up, but they have often been centred around being the only woman in male-dominated spaces. “At different levels, from rural communities, local government, to directors of organisations, it is often men who are in charge. Frequently, men are reluctant to work with a woman. They think that because I am a woman I am not as knowledgeable.”

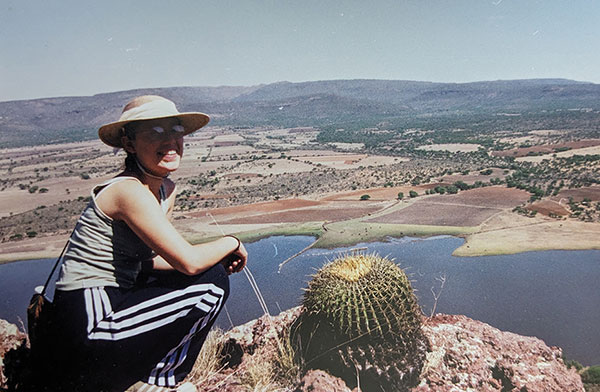

Maru conducting fieldwork in a semi-desert area of Mexico.

Maru says, though, that academia in general has been a very positive experience. “There can be hard days, but I am surrounded by good, supportive people.”

Community is very important to Maru, and she stresses how vital it is to have people to speak with about the harder parts of research. “I would say to anybody, but especially to women who want to pursue a career in science, surround yourself with a good community and speak to them about your challenges. Women in science often feel that they cannot talk about their work-related challenges because in a male-dominated environment, the perception is that it makes you look weak, insecure. But that is not true. So, surround yourself with good, supportive people and speak to them about your struggles. One of the most important things in science is the community and network you build.”

Maru adds that by having the support of mentors in her early career, she has been able to become a supportive mentor herself. “It’s important to pay it forwards, to be that person for someone else,” she says. “The path of research in science is a path of discovery, and it is hard, but it is also exciting and inspiring, where you can solve grand challenges, help society, and help the planet.”

About the Author

Beki Hooper is a freelance writer and researcher, with a PhD in animal cognition. Her science writing has appeared in numerous publications, including The Conversation, BOU Magazine and Psychology Today, where she writes a blog about the minds, relationships and behaviours of animals. She is also a Pushcart Prize nominated poet, with poems published and upcoming in multiple international literary magazines and anthologies. She lives in Devon, and when she isn't writing she is most often found wandering Dartmoor or swimming in the sea. You can follow her on Twitter @BekiHooper.