Interview with a Soapbox Scientist: Dr. Lauren Biermann

Dr. Lauren Biermann, a researcher at Plymouth Marine Laboratory, has always been infatuated with the ocean. “I grew up in South Africa, and one of my first memories is looking into a rockpool on a South African beach, seeing a fish in there, and my brain just exploding with joy!” Rather than looking at the ocean up close, as she did as a child, Lauren now spends most of her time looking down at the ocean from space. She uses satellite imagery to understand what’s going on in our seas, with research topics that range from monitoring the movement of invasive seaweed in the Caribbean, to examining underwater volcanic eruptions, to detecting plastic litter accumulating on our river and ocean surfaces. She does this global-scale science all from her office in Devon, using a vast bank of publicly available data that lets her watch the world – in real-time – from above.

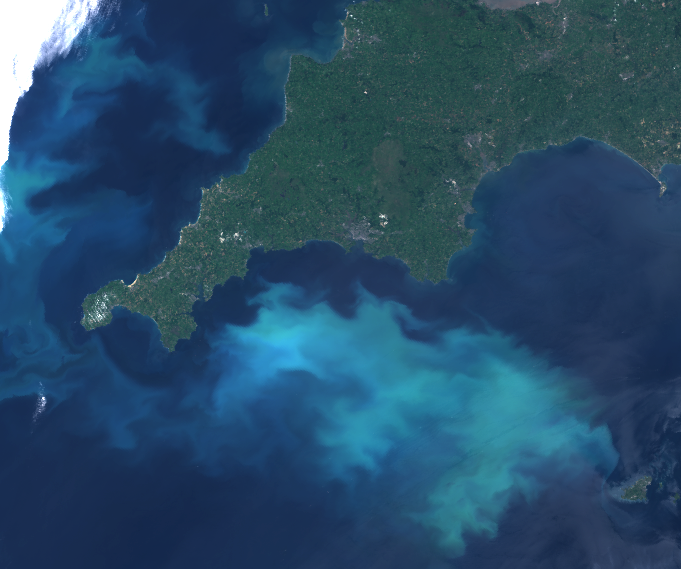

A strong but harmless coccolithophore bloom that developed off the Southwest coast of the UK in June 2020. The scene was captured by the OLCI (Ocean and Land Colour Instrument) sensor aboard the EUMETSAT Sentinel-3 satellite.

Lauren doesn’t call herself a biologist or a physical oceanographer, although her work branches into both fields. “Using satellite data, I help to answer questions on topics that span several areas of science, but they all have one theme in common: monitoring change.” For example, Lauren has used satellite imagery to solve a puzzle that was mystifying her fishery colleagues: what was causing certain species of fish to change their distribution? By tracking fishing vessels – from space – Lauren could record when the boats were travelling and when they stopped. “If you treat a boat like a marine predator, you understand that it only stops when it is ‘feeding’. So, you can use boat movement patterns as an indicator of where the fish are.” Using this information, Lauren could then ask what environmental measurements lined up with fish movement. She found that the best explanation of fish movement was sea surface temperature: where the warmer surface temperatures were, the fish tended to be. “The coolest thing was that all that data was just there, free for anyone to use. And with it, we managed to figure out the answer to this puzzle. That’s what I love about science – I love putting pieces of the jigsaw together.”

An image of underwater sand dunes and ripples on the Great Bahamas Bank, made using optical data collected by the ESA Sentinel-2 satellite.

Lauren first became interested in using satellite data as a tool to answer research questions during her PhD at the University of St Andrews. “I just found it beautiful – being able to observe things at this global scale, over these long timespans.” She compared learning to use the tools required to work with satellite data to learning to drive a car. There was a long period of time during her Master's degree where she was learning each little bit, akin to learning how to change gears, which mirrors to look in, how to park. Then, finally, she was let loose on the open road. “That’s when I really fell in love with it. When I was free to explore, choose my direction and find things out myself.”

In 2021, Lauren won the prestigious Blue Marine and BOAT International Ocean Award for Original Scientific Contribution following her incredible discovery that patches of plastics in coastal waters could be detected and identified using satellite imagery. This has helped to change the way that ocean plastics are observed, with the European Space Agency investing resources into monitoring plastics in this way. One might expect this to be the highlight of Lauren’s career, and although she says it was amazing to receive the award, she tells me that teaching has been her real highlight. “Giving other people the skills to use these tools is so rewarding. And especially, being able to teach people who traditionally couldn’t take these classes. We switched entirely to online teaching during the pandemic, and so many students – parents, people who needed to juggle their studies with other work, people who had a disability – told me they couldn’t have taken my course before we moved to virtual classrooms. Now we do everything with accessibility in mind, and I love that we can be more inclusive. Diversity is key to good science, and we need more of it: more women, more minorities, more neurodiversity. The more perspectives we have, the more diverse the ideas we have, the more creative we are and the better our science is going to be.” She swings back to thinking about science as a jigsaw puzzle. “Science is like a bunch of people with different skills all working on a jigsaw puzzle together. It’s teamwork. And we need a diverse team to be the best we can be.”

I ask Lauren if working with such global-scale, long-term data has changed her perspective or understanding of the world we live in. “I think I’m more aware of the changes that are happening on local and global scales,” she says. “But then, I challenge anyone who pays attention to the natural world to say they haven’t noticed changes. Humans have had such an extensive impact in a short period of time, it’s almost impossible not to notice.” On the flipside to noticing the negative impacts, Lauren believes that looking at the world from space can also inspire awe and wonder and a better understanding of our planet. “We’re so focussed on what’s in front of us all the time – it can be hard to step back and see things in context. Satellite imagery lets us do that. It lets us see the true scale of things.”

Da Nang in Vietnam, from optical data collected by the ESA Sentinel-2 satellite.

If you’d like to explore some satellite imagery, you can check out underwater volcanic eruptions and new island formation, or North Sea windfarms and boats (looking like stars). It’s all entirely free, and you can move around to zoom in on anything. “You can look across the whole globe if you want to, but honestly,” Lauren says, “just zooming into a beach near your house and counting the paddleboards is a lot of fun too!”.