- Home

- Our institutes

- Environment and Sustainability Institute

- News and events

- Challenge of the Month

ESI Challenge of the Month

Dr Eunice Oppon (Senior Lecturer in Sustainability and Business Analytics), has taken up the ESI Challenge of the Month for June 2025.

Relevant research:

Oppon et al. (2024) — "Sustainability performance of enhanced weathering across countries: A triple bottom line approach," Energy Economics

Oppon et al. (2023) — "Macro-level economic and environmental sustainability of negative emission technologies; ; Case study of crushed silicate production for enhanced weathering" Ecological Economics

Oppon et al. (2023) — "Towards sustainable food production and climate change mitigation: an attributional lifecycle assessment comparing industrial and basalt rock dust fertilisers," The International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment

Acquaye et al. (2018) — "A quantitative model for environmentally sustainable supply chain performance measurement," European Journal of Operational Research

Oppon et al. (2018) — "Modelling multi-regional ecological exchanges: The case of UK and Africa," Ecological Economics

Learn more about Enhanced Weathering Africa Partnership Project.

Dr Eunice Oppon will deliver the ESI Challenge of the Month talk "Climate, Crops, and Crushed Rocks: Mapping the Sustainability of Enhanced Weathering from Mine to Field" on Monday 30 June 2 - 3pm in the ESI Trevithick Room.

Enhanced weathering (EW)—the application of crushed silicate rocks to agricultural soils has emerged as a promising climate solution for carbon dioxide removal, while potentially improving soil fertility and crop yield. But how sustainable is this process across its full life cycle, from mineral extraction to application on farms?

In this talk, I explore the multi-dimensional sustainability of enhanced weathering using quantitative modelling techniques such as life cycle assessment (LCA) and multi-regional input-output (MRIO) analysis. These methods allow us to map environmental, economic, and social impacts across sectors, geographies, and stages of the EW value chain.

Drawing on recent case studies from both developed and emerging economies, I will examine:

- The climate mitigation potential and trade-offs of large-scale crushed rock deployment

- The resource demands and emissions linked to mining, processing, and transport of basalt

- The social and economic dimensions, including labour impacts and implications for smallholder farmers

- The broader question of ecological unequal exchange, where Global South regions bear environmental burdens for Global North climate goals

This interdisciplinary talk invites geologists, soil and agricultural scientists, mining researchers, economists, and sustainability scholars to reflect on how enhanced weathering intersects with global efforts to deliver just, viable climate solutions.

#esiChallengeOfTheMonth

Please email esidirector@exeter.ac.uk if you would like a Teams link to join this talk remotely.

Previous challenges

Dr Sarah Crowley, Senior Lecturer in Human & Animal Geography, took up the very first ESI Challenge of the Month for September 2024.

Click here to view her profile page.

Relevant research:

Some of her work under 'introduced species'

- Crowley, S. L., Hinchliffe, S., & McDonald, R. A. (2019). The parakeet protectors: understanding opposition to introduced species management. Journal of environmental management, 229, 120-132.

- Crowley, S. L., Hinchliffe, S., & McDonald, R. A. (2017). Conflict in invasive species management. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 15(3), 133-141.

- Her current project under this theme is Fish Futures: Reimagining freshwater ecosystem management in Aotearoa.

Some of her work under 'reintroduced species'

- White, R. L., Jones, L. P., Groves, L., Hudson, M. A., Kennerley, R. J., & Crowley, S. L. (2023). Public perceptions of an avian reintroduction aiming to connect people with nature. People and Nature, 5(5), 1680-1696.

- Dando, T. R., Crowley, S. L., Young, R. P., Carter, S. P., & McDonald, R. A. (2023). Social feasibility assessments in conservation translocations. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 38(5), 459-472.

- Crowley, S. L., Hinchliffe, S., & McDonald, R. A. (2017). Nonhuman citizens on trial: The ecological politics of a beaver reintroduction. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 49(8), 1846-1866.

- Her project under this theme: Social feasibility work for the South West Wildcat Project.

Some of her work under 'domestic animal management'

- Cecchetti, M., Crowley, S. L., Goodwin, C. E., & McDonald, R. A. (2021). Provision of high meat content food and object play reduce predation of wild animals by domestic cats Felis catus. Current Biology, 31(5), 1107-1111.

- This study was among the 5 most popular scientific papers of March 2021 in the Nature Index journals

- It was featured in The Guardian, CNN, Science and more!

- Crowley, S. L., Cecchetti, M., & McDonald, R. A. (2020). Our wild companions: Domestic cats in the Anthropocene. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 35(6), 477-483.

- Crowley, S. L., Cecchetti, M., & McDonald, R. A. (2020). Diverse perspectives of cat owners indicate barriers to and opportunities for managing cat predation of wildlife. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 18(10), 544-549.

- Read the University press release

- This study was featured in the Independent, yahoo news, CNN, iNews, Science Daily and the IFL Science.

- Her projects under this theme:

- The Cat Accord: Developing shared guidance on domestic cat management

- RENEW "Paws for Thought" ExCases project on dog walking and the environment

- Cats, Cat Owners, and Wildlife (2017 - 2020)

Dr Sarah Crowley delivered the ESI Challenge of the Month talk "The Species in Between: negotiating animal management in a changing world" on Monday 30 September 1 - 2pm in the ESI Trevithick Room.

Do parakeets belong in Britain? Do Scottish wildcats belong in England? Do domestic cats belong outdoors? Much of my work focuses on disagreements and negotiations about which animals belong where, and about whether or how people should intervene in the lives of other species. The subjects of these debates are often ‘liminal’ animals, living on the thresholds between contested categories: native and non-native, wild and domestic, pet and pest. These categories reflect complex human ideas about belonging, which draw on natural and cultural histories, ecological and social interactions, and concerns for the future of disturbed and changing ecosystems. This seminar is based on ten years of research into the social dimensions of managing introduced, reintroduced, and domestic animals in the UK. I will draw on a range of case examples, including protests to protect urban parakeets, scientific debates about the provenance of wildcats and white storks, and neighbourly disputes over outdoor cats. I will explain and explore the concept of species belonging, demonstrate why this matters, and argue that where an animal belongs should always be a matter open to negotiation.

#esiChallengeOfTheMonth

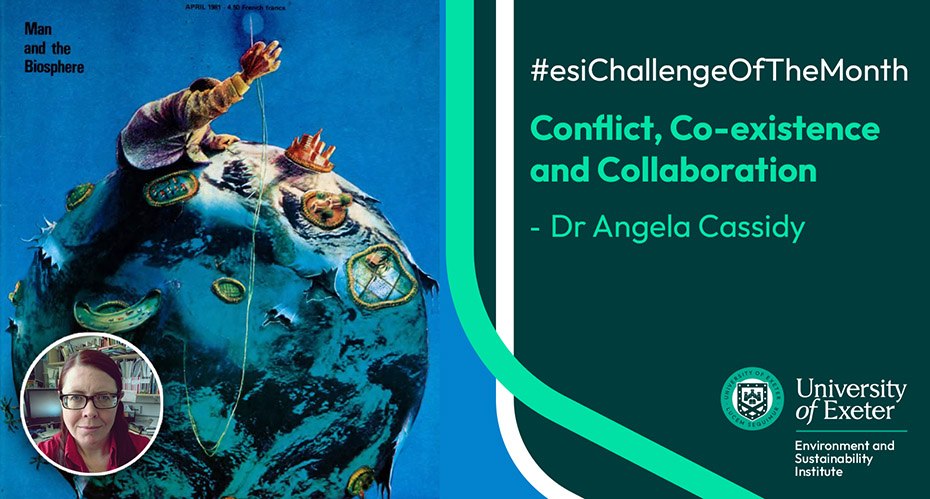

Dr Angela Cassidy, Associate Professor in Science and Technology Studies, took up the ESI Challenge of the Month for October 2024.

Click here to view her profile page.

Relevant research:

Conflict:

- Why do some scientific controversies take place ‘in public’? Sometimes, ‘it’s the politics, stupid’ argument isn’t really about ‘the science’. This piece by Dan Hicks argues this is the case with GMOs, vaccine debates and climate change. [Hicks, D. J. (2017). Scientific Controversies as Proxy Politics. Issues in Science & Technology, 33(2)].

- ‘Science push.’ Scientists put work into public communication for lots of reasons. In the case of ev-psych, it was to help them establish legitimacy, which they did not have inside psychology. Scicomm is a multidirectional conversation! [Cassidy, A. (2006). Evolutionary psychology as public science and boundary work. Public Understanding of Science, 15(2), 175-205].

- ‘Media pull.’ At the same time, a (literally) sexy subject helps. Why media loved evolutionary psychology? Gender essentialism and public dust-ups sell! [Cassidy, Angela. 2007. ‘The (Sexual) Politics of Evolution: Popular Controversy in the Late 20th-Century United Kingdom.’ History of Psychology 10(2):199–226]

Co-existence:

- Public controversy over Bovine TB and badger cull involves politics, science push, media pull AND a*very long backstory. This public scientific controversy has been going on for over 50 years, and in the UK, we’ve been arguing about badgers for a lot longer than that: [Cassidy, Angela. 2019. Vermin, Victims and Disease: British Debates over Bovine Tuberculosis and Badgers. Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan; Springer International. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31961627/.]

The oldest historical source used for this research is the Exeter Book (scanned and made available online by Exeter Digital Humanities, with the original found at the Exeter Cathedral), which dates to c. 970 AD. Riddle 15 is tells the story of a hunted animal defending its family in a ‘hole in the hill’ and is generally thought to be about badgers.

- At the same time, people love to feed other animals, often because we foster care and social connections with others by sharing food. Anthropologists call this ‘commensality’, while zoologists think about ‘commensalism’ and its importance for domestication processes. Dr Cassidy is part of the Animal Feeding project, funded by the Wellcome Trust. It explores the causes and consequences of people feeding other animals in past and present.

The project team have created a Modern Bestiary which is being exhibited at the Museum of English Rural Life (MERL) in collaboration with the artists Rebecca Jewell and and Sandy Sykes.

Collaboration

- Given that disciplinary specialists and human/nonhuman co-existence can turn so easily towards conflict, how to regear to collaboration? The RENEWing Biodiversity partnership is exploring this question at multiple levels: https://renewbiodiversity.org.uk/.

RENEW starts from the proposition that to address the biodiversity crisis we’re in with due urgency, we need to turn traditional conservation logic inside-out and place ‘people in nature.’ RENEW has ground breaking collaborations: National Trust as Co-Investigators, over 30 non-academic partners, Social Science and Humanities researchers on equal terms with natural scientists and a shared research agenda. Dr Cassidy is Co-Investigator for the X3 Collaboration in Practice theme, exploring how interdisciplinarity works everyday.

- Environmental scientists have been trying to do this since the 1960s. For example, the UNESCO Man and the Biosphere image in the 1980s, stitching the planet back together via interdisciplinary research. Are we reinventing the wheel? Our research is finding out via collaboration with the British Library Oral History department.

- RENEW uses 'embedded STS' approach, studying collaboration in real time, making creative interventions to help people build relationships, think across disciplines, reflect on practices and explore care for each other and biodiversity.

- The RENEW project also makes practical recommendations, based on research and 'grey' policy literature along with first-hand accounts. For example, start with a shared research agenda rather than expecting some disciplines to solve the questions and problems defined by another. Read more.

Dr Angela Cassidy delivered the ESI Challenge of the Month talk "Conflict, Co-existence and Collaboration" on Monday 21 October 1 - 2pm in the ESI Trevithick Room.

Why do we have academic disciplines and what happens when they disagree? How do people co-exist with other animals? Can interdisciplinarity work? These are the kinds of challenge I engage with in my research, which is all about science, borders, boundaries and the spaces in-between. The talk will start with the theme of ‘Conflict’, exploring public knowledge controversies and drawing out how and why some scientific disagreements are played out in the wider public sphere, using evolutionary psychology and bovine TB as examples. The case of badger/TB (alongside a small bestiary of other examples) will in turn be used to think through the historical dynamics of controversies; how human-animal relationships have changed over the past century; and how food may be key in shifting relations from conflict to co-existence. Finally, I will reflect upon my ongoing work investigating interdisciplinarity – research that reaches beyond disciplinary boundaries. Drawing upon oral histories of collaborative experiences, combined with our team’s ‘embedded’ study of interdisciplinarity in the RENEW(ing) Biodiversity project, I will outline practices that help people work together across multiple fields of expertise, and key factors that can block their paths.

#esiChallengeOfTheMonth

Dr Jamie Hampson, Associate Professor in the History department, Humanities and Social Sciences, Cornwall, took up the ESI Challenge of the Month for November 2024.

Click here to view his profile page.

Relevant research:

An internationally known scholar of Indigenous heritage, rock art, and symbolism, Dr Hampson has documented and analysed more than 1600 rock art sites in southern Africa, Australia, the Americas, India, and Europe. He has published the following books on Rock Art:

- Hampson, J., Goldhahn, J., & Challis, S. (2022). Powerful pictures: Rock art research histories around the world. Archaeopress.

- Hampson, J., & Rozwadowski, A. (2021). Visual Culture, Heritage and Identity: Using Rock Art to Reconnect Past and Present. Archaeopress.

- Hampson, J. (2016). Rock art and regional identity: a comparative perspective. Routledge. [First edition published in 2015; paperback published in 2021.]

Since 1999, Jamie has delivered more than one hundred conference papers, and organised three major conferences that span history, heritage studies, environmental humanities, archaeology, and anthropology. Some of his recent papers:

- Hampson, J., Iriarte, J., & Aceituno, F. J. (2024). 'A World of Knowledge': Rock Art, Ritual, and Indigenous Belief at Serranía De La Lindosa in the Colombian Amazon. Arts, 13(4), 135.

Read the University press release here. This was also featured in the Newsweek. - Robinson, M., Hampson, J., Osborn, J., Aceituno, F. J., Morcote-Ríos, G., Ziegler, M. J., & Iriarte, J. (2024). Animals of the Serranía de la Lindosa: Exploring representation and categorisation in the rock art and zooarchaeological remains of the Colombian Amazon. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 75, 101613.

- Hampson, J. & Challis, S. Cultures of appropriation: rock art ownership, Indigenous intellectual property, and decolonisation. In: Moro Abadia, Conkey, & McDonald (eds), Deep-Time Images in the Age of Globalization: Understanding Rock Art in the 21st Century, 275–288. New York: Springer.

Dr Hampson's three large interdisciplinary research grants (£1.3 million in total) were and are supported by Indigenous groups and government bodies, and they continue to have international impact. Here is a recent grant award:

- Dr Jamie Hampson has been awarded £225,000 as a Co-PI with physicist Dr Tessa Charles (University of Liverpool/ Australian Synchrotron) and archaeologist Dr Courtney Nimura (Ashmolean Museum, Oxford) on a UKRI Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council interdisciplinary project.

NoMAD (Non-destructive Mobile Analysis and imaging Device) draws on technology developed for particle accelerators to bring scientific analysis techniques to Indigenous rock art and other remote heritage sites. The project focuses on rock art – a crucial part of our shared global cultural heritage – and the design and development of a portable particle accelerator. This project is a world-first, revolutionary in the fields of physics and cultural heritage management.

Dr Jamie Hampson delivered the ESI Challenge of the Month talk "Images of power: why should we care about Indigenous rock art?" on Monday 25 November 1 - 2pm in the ESI Trevithick Room.

Sacred Indigenous rock paintings and engravings are found in different landscapes in almost every country around the world. Some motifs are at least 75,000 years old; some were painted yesterday.

We do not always know exactly what the rock imagery means, but thanks to intertwining strands of evidence we do know a great deal – especially in regions where the descendants of the original artists still survive. Indeed, rock art motifs were – and often still are – ‘powerful things in themselves’, and an integral part of sacred Indigenous heritage. Tragically, however, rock art in some parts of the world is threatened by industrial development and climate change.

In this talk, I draw from 25 years of archaeological and anthropological fieldwork in southern Africa, the Americas, and Australia.

#esiChallengeOfTheMonth

Prof Ilya Maclean, Applied Ecologist at the Centre for Ecology and Conservation, took up the ESI Challenge of the Month for January 2025.

Click here to view his profile page.

Relevant research:

Researchers argue that abrupt biodiversity losses can be driven by populations sharing similar tolerances to warming in The Conversation. This study in the Royal Society Publishing is part of the discussion meeting issue ‘Bending the curve towards nature recovery: building on Georgina Mace’s legacy for a biodiverse future.'

Prof Maclean delivered the ESI Challenge of the Month talk "The art and science of prediction" on Monday 27 January 1 - 2pm in the Daphne du Maurier seminar room M.

With an urgent need to reverse the rapid destruction of the biodiversity and ecosystems upon which humans depend, it is often useful to make accurate forecasts to enable targeted and timely interventions. In this month's challenge, I delve into the question of whether - and how - researchers make predictions about the impacts of environmental change. I contend that while most predictions are wrong, some are useful and the central challenge, then, is to make them less wrong and more useful. Using species responses to climate change as a case study, I demonstrate how integrating physics, biology, socio-economics and comedy can enhance the accuracy, utility and memorability of predictions. Along the way, I question some prevailing paradigms about how predictions are typically made and will also cover our recent contribution to a special issue of Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society dedicated to ‘Recovering nature’ in commemoration of the life and work of the brilliant Georgina Mace. Georgina was Editor-in-Chief of this journal from 2008 until 2010 and was the first female Editor-in-Chief of a Royal Society journal. You can read about our work here and more of papers dedicated to her legacy here.

#esiChallengeOfTheMonth

Dr Laura Colombo, Senior Lecturer in Sustainable Futures, took up the ESI Challenge of the Month for February 2025.

Click here to view her profile page.

Relevant research:

The University of Exeter has been a pioneer in working towards bridging the ecology - business studies divide. Dr Laura Colombo is the Programme Director for the interdisciplinary BSc Business and Environment programme. The programme is built on: Sustainable business, Environmental science and Environmental justice.

"What are business schools for? Who are they for? For what future?" Sophie talks to Dr Laura Colombo about the need to transform management education for a sustainable future. Listen to the podcast now.

Some relevant work by colleagues in the space of bridging business and ecology:

- This article clearly and unequivocally states that business-as-usual contributes to environmental crises because of its focus on profit. How can business studies learn from natural system processes to enhance value creation and better steward the natural environment?

- This article argues that the organisation studies can no longer ignore the current global climate emergency. How does the discipline need to be rethought in a world approaching 50 degrees?

- This article argues that incremental and accommodative forms of responsible management learning and education are at odds with the urgency, nature, and magnitude of the climate crisis, and calls for “radicalising” management education.

Dr Laura Colombo's recent research on this topic:

- This article discusses how business schools can transform to address the pressing social and ecological challenges of our time. Drawing on insights from social-ecological systems and social innovation research, this article argues that management education must shift from a narrow focus on market efficiency to a broader, civic-oriented approach.

- This editorial calls for the development of a social-ecological approach to management learning and education, considering business, society, and nature as nested systems: without society, there is no business; and without nature, there is no society, hence no business. This has important implications for how and what we teach in business schools.

Dr Colombo delivered the ESI Challenge of the Month talk "Bridging the Divide: Integrating Ecology and Business for a Sustainable Future" on Monday 27 January 1 - 2pm in the ESI Trevithick Room.

As Kenneth Boulding famously quipped: “Anyone who believes that growth can go on forever is either a madman or an economist.” Ecological economics has long recognised that the economy cannot be considered in isolation from the social and environmental systems in which it is embedded. After all, as their shared etymological roots remind us, the words “economy” (oikos + nomos) and “ecology” (oikos + logos) are linguistic siblings.

While a dialogue between ecology and economics has long been established, business studies have largely remained estranged from this conversation. However, this is beginning to change. In recent years, in management and organisation studies scholarship, there has been a growing recognition that business – like all human activity – is embedded in, and dependent upon, complex living systems. This realisation carries profound implications for what and how we teach in business schools. Yet, much of this territory remains uncharted.

This month’s challenge is an invitation for ecologists and business scholars to come together. Forty-three years after the Symposium on “Integrating Ecology and Economics” laid the foundation for ecological economics, it is time to ask: how can we integrate ecology and business studies? What can business learn from ecology, and what might ecology learn from engaging with business?

#esiChallengeOfTheMonth

Dr Chris Kaiser-Bunbury (Senior Lecturer at the Centre for Ecology and Conservation) accepted the ESI Challenge of the Month for March 2025.

Click here to view his profile page.

Relevant research:

Hear Dr Kaiser-Bunbury talk about insect decline and the impact on our food supplies on the BBC Radio 4 documentary Apocalypse How: Insectageddon (20.30 mins onwards).

A few selected relevant papers showing Dr Kaiser-Bunbury's background in network ecology and conservation/ restoration, learning from insights from tropical communities and applying a similar approach to urban landscapes in the UK:

- Kaiser-Bunbury CN, Blüthgen N. 2015. Integrating network ecology with applied conservation: a synthesis and guide to implementation. AoB Plants, 7: plv076.

- Kaiser-Bunbury CN, Mougal J, Whittington AE, Valentin T, Gabriel R, Olesen JM, Blüthgen N. 2017. Ecosystem restoration strengthens pollination network resilience and function. Nature, 542: 223-227. View the press release here.

- Kaiser-Bunbury CN. 2019. Restoring plant-pollinator communities: using a network approach to monitor pollination function. In: Veitch CR, Clout MN, Martin AR, Russell JC, West CJ, eds. Island invasives: scaling up to meet the challenge. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN.

- Costa A, Heleno R, Dufrene Y, Huckle E, Gabriel R, Doudee D, Kaiser-Bunbury CN. 2022. Seed dispersal by frugivores from forest remnants promotes the regeneration of adjacent invaded forests in an oceanic island. Restoration Ecology, 30: e13654.

- Poole O, Costa A, Kaiser-Bunbury CN, Shaw RF. 2025. Pollinators respond positively to urban green space enhancements using wild and ornamental flowers. Insect Conservation and Diversity, 18: 16-28.

Dr Chris Kaiser-Bunbury delivered the ESI Challenge of the Month talk "On the art of conserving pollinators: the role of gardeners" on Monday 31 March 1 - 2pm in the ESI Trevithick Room.

Insect pollinators are in decline worldwide, threatening global food production and the diversity of plant communities that depend on pollinators for reproduction. As a conservation ecologist using interaction networks to understand the impact of pollinator decline on ecological communities, my research aims to understand how we can best halt the erosion of insect abundance and diversity. While our ability to monitor changes in pollinators and pollination in human-modified landscapes is essential for effective management and protection, the engagement and actions of the general public potentially have the biggest impact on pollinator diversity in such landscapes.

Residential gardens are now known to be important refuges for pollinators, as agricultural lands are becoming increasingly hostile environments for these beneficial insects. The challenge is to engage and empower residential gardeners in managing these important habitats for pollinators.

I will present an exciting interdisciplinary approach to address the pollinator crisis. Our new project explores the power of art and algorithm-derived planting designs to create networks of optimal foraging habitats for pollinators across a semi-urban environment and studies the role that garden owners can play in actively supporting and monitoring pollinators in their gardens. The project combines art, social science, philosophy and ecology to improve pollinator diversity in residential gardens and transform human-nature interactions by enabling gardeners to engage in evidence-based methods for biodiversity conservation.

#esiChallengeOfTheMonth

Dr Bridget Watson (Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Centre for Ecology and Conservation) accepted the ESI Challenge of the Month for May 2025.

Click here to view her profile page.

Relevant research:

Current funding: Biological and Biotechnological Research Council (BBSRC) Discovery Fellowship, since 2023: “Determining the role of defence systems in the evolution of the Azospirillum-wheat mutualism to enhance crop yields for sustainable agriculture.” Read more.

Current funding: The Royal Society Research Grant, since 2025: “Examining the widespread plant growth promoting benefit of Azospirillum spp.”

For an overview of the plant microbiome and its role in sustainable agriculture, click here.

For an introduction to Azospirillum spp., beneficial bacteria that support plant growth, click here.

Watson, B. N. J., Pursey, E., Gandon, S., & Westra, E. R. (2023). Transient eco-evolutionary dynamics early in a phage epidemic have strong and lasting impact on the long-term evolution of bacterial defences. PLoS biology, 21(9), e3002122.

Hampton, H. G., Watson, B. N., & Fineran, P. C. (2020). The arms race between bacteria and their phage foes. Nature, 577(7790), 327-336.

Watson, B. N., Staals, R. H., & Fineran, P. C. (2018). CRISPR-Cas-mediated phage resistance enhances horizontal gene transfer by transduction. MBio, 9(1), 10-1128.

Dr Bridget Watson delivered the ESI Challenge of the Month talk "Growing plants sustainably: harnessing the power of the soil microbiome" on Monday 2 June 1 - 2pm in the ESI Trevithick Room.

Growing sufficient food to feed the world is a huge task, especially when faced with a growing population and the unpredictability that comes with climate change. However, many current agricultural practices can be damaging to the environment, as intensive farming can deplete soils, reducing soil fertility. In addition, the use of synthetic fertilisers and pesticides can pollute water ways. Going forward, agricultural production must become more sustainable to ensure that the land can continue to provide for future generations. Addressing this complex challenge will require a multifaceted approach, but focusing on the microorganisms in the soil and harnessing their ability to support plant growth will be a key component.

My research focuses on soil microbes that naturally support plant health and aims to bridge gaps in our understanding of plant-microbe interactions so we can effectively use microbes as tools for sustainable agriculture. More specifically, I study beneficial soil bacteria from the Azospirillum genus, alongside wheat and related plants, as a model system to understand the mechanisms underpinning how bacteria promote plant growth. Further, my work examines how bacteria evolve and adapt in the dynamic soil environment, plus how plant-bacteria interactions are influenced by various factors in the complex soil environment.

#esiChallengeOfTheMonth