Project lead

Partners

Prof. Christoph Werner

Dr. Fahad Bishara

Prof. Chander Shekhar

Project staff

Mehrbod Khanizadeh

Dr Dominic Vendell

Dr Elizabeth Thelen

Project Collaborators

Fouzia Farooq Ahmed

Prachi Deshpande

Mr Khizar Jawad

The project is funded by a €1.5 million Starting Grant by the European Research Commission.

Forms of Law in the Early Modern Persianate World, 17th-19th centuries

The project is led by Dr Nandini Chatterjee and will investigate how people in the Persianate world thought about law and their efforts and ideas to secure rights and justice. Dr Nandini Chatterjee will work with project partners including Prof. Christoph Werner, Centre for Near and Middle Eastern Studies, Philipps-Universität Marburg, Germany; Dr. Fahad Bishara, Department of History, University of Virginia, U.S.A. and Prof. Chander Shekhar, Department of Persian, Delhi University, India.

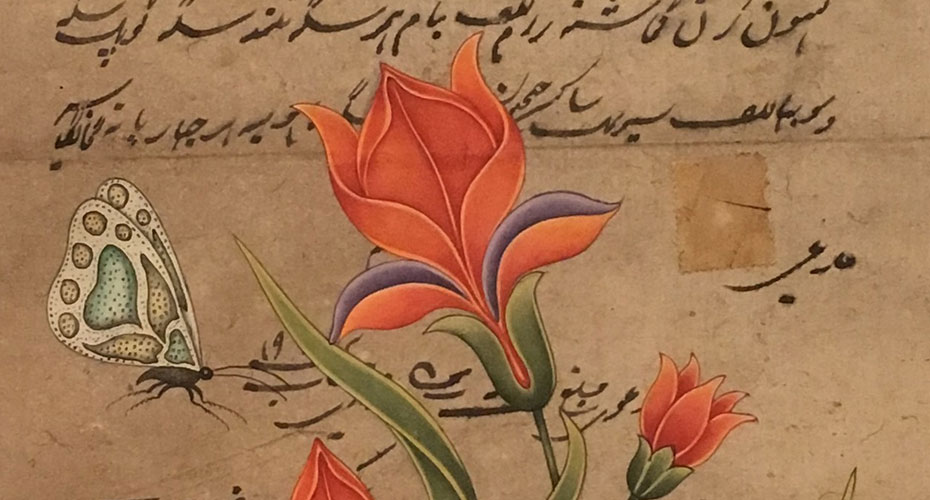

Once upon a time, Persian or Farsi was the language of high culture, literary production, and administrative and legal record-keeping across a vast section of the world, stretching from present-day Bangladesh in the east to Bosnia in the west. Today, Persian is still spoken by people in a number of countries, but it has official status only in Iran, Tajikistan (under the name: Tajiki) and Afghanistan (under the name: Dari). This project is about that lost world, which Marshall Hodgson called Persianate. Delving into that world, where Persian was the language of cosmopolitan culture and also legal record, we will investigate how people – commoners to kings – thought and spoke about law, how their cultural baggage determined their ideas and efforts to secure rights and justice. We will do so by looking at Persian-language and bi-lingual legal documents, studying their forms, their favourite formulae and the formularies that provided the models for such legal writing.

Research methods

Much of this project about law and legal documentation is also about reading and writing, and about language use in a multi-lingual world. We will study legal documents written in Persian and associated languages produced in five major linguistic-cultural zones stretching from the Indian subcontinent to Iran and the northern and western Indian Ocean. We will study their vocabularies, their scripts, their graphic elements (such as seals and symbols) and by doing all this, we will try to understand how and why people used such linguistically complex forms to record and assert their entitlements.

Our focus is on the ordinary users of law, rather than on specialists. By this we mean that while we will look at the writings of jurists, and through them remain aware of the wider world of Islamic jurisprudence and documentation, our aim is to understand what protagonists like the petty Bengali landlord, the Gujarati merchant and the bazaar scribe thought about recognisable entitlements, obligations and transactions, and how to record them. We will also study how, in different ways for different parts of the world covered by this project, the encroachment of European power, and in some cases, political control, inflected such writing and recording practices, and try to understand what that meant about changes in ideas about the law.

Project staff and upcoming opportunities

The project has appointed two postdoctoral research assistants (PDRs), to undertake research on materials related to two defined linguistic sub-zones covered by the project: Marathi and Rajasthani. The appointed PDRs are Dr Dominic Vendell (Ph.D., Columbia University) and Dr Elizabeth Thelen (Ph.D., University of California at Berkeley). They have begun work in July and September 2018, respectively.

Mr Khizar Jawad, Assistant Professor, Forman Christian College Lahore has been appointed the first Pakistan based non-stipendiary research associate of the project, and will work on Persian documents produced during the Khalsa regime in the Punjab. Mr Jawad is in the UK June-August 2018.

Dr Fouzia Farooq Ahmad, Lecturer, Quaid-i Azam University, Islamabad is the second Pakistan-based research associate of the project, and will work on fath-namas as a genre.

Project outputs

During the course of this project, we will organise two intensive workshops, one at Exeter and the other at Marburg, each of which will be twinned with a larger conference. We are aiming to produce several collective and individual academic outputs, including a major digitisation project, which will enhance an existing database of Persian-language legal documents called Asnad.